Search This Blog

18 May 2012

06 May 2012

I've known a Heaven, like a Tent –

I've

known a Heaven, like a Tent –

To

wrap its shining Yards –

Pluck

up its stakes, and disappear –

Without

the sound of Boards

Or

Rip of Nail – Or Carpenter –

But

just the miles of Stare –

That

signalize a Show's Retreat –

In

North America –

No

Trace – no Figment of the Thing

That

dazzled, Yesterday,

No

Ring – no Marvel –

Men,

and Feats –

Dissolved

as utterly –

As

Bird's far Navigation

Discloses

just a Hue –

A

plash of Oars, a Gaiety –

Then

swallowed up, of View.

F257

(1861) 243

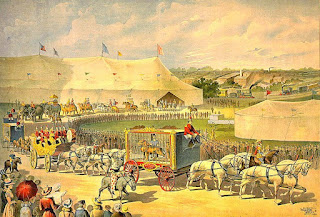

Some

people, and I suspect Emily Dickinson is one of them, can find a little bit of

heaven in a sunset, a soiree, a garden, or a dusty path through a meadow. In

this poem she compares the lush ephemerality of these brief heavens to a

circus. Amherst would no doubt have seen a few traveling circuses and the shows

would have been great attractions. The circus would arrive with a parade:

beautifully outfitted prancing horses, carriages pulling caged lions and

tigers, acrobats marching and twirling, and elephants plodding along with their

tenders. The tents would go up overnight and then the magic would begin – only

to be taken down and removed a day or two later when the circus moved on.

|

| Everyone watches as the circus leaves town |

The

poet’s heaven came and went like that except that it was more silent. There was

no sound of hammers or all the hustle and bustle of packing up and leaving.

Instead, the Heaven wrapped “its shining Yards,” plucked itself up by the

stakes, and disappeared. It left “No Trace – no Figment” of what was so

dazzling the day before. The acrobats and feats of courage and skill were gone.

The

poet likens the absence of the divine circus to “miles of Stare” – a landscape

you might stare across for miles without seeing the hoped-for thing. The phrase

implies longing and wondering, “stare” being more intense than “gaze.” This

stare might characterize the children staring after the circus train and

carriages disappearing from sight – its “Retreat.” The children might have the

same sense of awe and loss as the poet searching the horizon for the lost

heaven.

In

the second stanza Dickinson frames the absence as the last glimpse of bird in

flight as it is “swallowed up” in the distance. She characterizes this as a

dissolving: the bird is first visible and then begins to fade against the

clouds and sky as it flies away. Finally it is just a hint of color, a slight

indication of movement. She describes this as the “plash of Oars” as if the

bird were rowing through the sky. She will use similar imagery in 1862 in the

familiar poem, “A Bird, came down the Walk.” In this poem the narrator feeds

the bird a crumb and then -

… he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home –

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless, as they swim.

The last fleeting sense of the bird before it

dissolves from view is “a Gaiety.” I picture the flowing, bounding flight of a

song sparrow – gay as can be! Once the bird is gone, all that remains is the “View.”

Dickinson’s

treatment of absence as “miles of Stare” and of as a swallowing “View” is slightly

disturbing. It is as if our eyes are looking into some vastness that is not

empty as it appears but somehow full of potential presence. We see something

marvelous or delightful. It disappears without a sound but the air has changed;

something still lingers from the circus disappearing in the horizon, the birds

fading against the sky. A space has been made that is now empty, much as the

empty corner still contains something of the easy chair that once sat so

comfortably there.

The Robin's my Criterion for Tune –

The

Robin's my Criterion for Tune –

Because

I grow – where Robins do –

But,

were I Cuckoo born –

I'd

swear by him –

The

ode familiar – rules the Noon –

The

Buttercup's, my Whim for Bloom –

Because,

we're Orchard sprung –

But,

were I Britain born,

I'd

Daisies spurn –

None

but the Nut – October fit –

Because,

through dropping it,

The

Seasons flit – I'm taught –

Without

the Snow's Tableau

Winter,

were lie – to me –

Because

I see – New Englandly –

The

Queen, discerns like me –

Provincially

–

F256

(1861) 284

You

see the line “Because I see – New Englandly” pop up from time to time in

discussions of Dickinson or other New Englanders or modified to suit whomever’s

personal vantage point is in question. It’s a great line! I think the poem is brimming

over with good lines, though. I’d be hard pressed to pick a favorite.

|

| Even though she became a queen, little Victoria would have been shaped by her English countryside |

The

central insight is more profound than the light treatment indicates on a quick

read. We are all probably much more products of our formative geographies than

we think. Some of us are “Orchard sprung” and so urban environments will never

feel completely natural. We grow up with robins or cacti or bougainvillea – or

subways, boom boxes, and house sparrows. Our brains form in response to what we

see around us at an early age. Even the Queen herself does not discern life on

the grand scale befitting a monarch. She, too, thinks of snowfall on the palace

grounds in winter, of foxes darting across the woods, of the song thrush and

nightingale. Did she love the fox and hate the fox hunt – or vice versa? Would that affect her impulses as a queen?

There

is nice concision in the beginning of the second stanza. The Nut (walnut or

acorn or other nut – doesn’t matter) comes with October, the month when in New

England trees drop their nuts. And this, the poet says, contains all the

seasons: Autumn when the nuts fall; winter as they get buried by an enterprising

squirrel or crow, spring as they send forth a new shoot, and summer as the

plant grows and matures, sending out its leaves.

The

poem has many internal rhymes and assonances as well as end rhymes and slant

rhymes that provide a nice flow and a rich sound. Some examples:

- Robin

/ Criterion / Tune all end on an ‘n’ and have other nice resonances;

- Cuckoo

of line 3 rhymes with itself and with “do” from the previous line.

- There’s

a nice spate of alliterative ‘b’s in the second half of the first stanza:

Buttercup, Bloom, Because, Britain, born

- “None

but the Nut” is nice in assonance and alliteration

- A

spate of ‘t’s trip through the second stanza: Nut, October, fit, it, flit,

taught, Tableau, Winter, to.

- There are various end rhymes and slant

rhymes, but a favorite is New Englandly with Provincially. What fun!

Content-wise,

the poem’s two stanzas treat first the particular plants and animals the

represent home to the poet, and in the second, the seasons. The last three

lines summarize the theme. "Provincially" belongs with the previous line, but Dickinson emphasizes it by placing it alone at the very end. The Queen is as part of her formative environments as is the poet. There's a bit of play in the word. The Queen has her provinces and colonies. When she sees "provincially" she is also seeing her domains. The implied corollary is that Dickinson has her own provinces and domains, too. Indeed, her gardens, woods, and orchard provide her with a rich world that her readers are still exploring.

04 May 2012

The Drop, that wrestles in the Sea –

The

Drop, that wrestles in the Sea –

Forgets

her own locality –

As

I, in Thee –

She

knows herself an incense small –

Yet

small – she sighs – if all – is all –

How

larger – be?

The

Ocean, smiles – at her conceit –

But

she, forgetting Amphitrite –

Pleads

– "Me"?

F255

(1861) 284

Dickinson

covers familiar ground here – the small water merging into a larger body and losing

its individuality. In F219, “My

river runs to thee,” she playfully asks the “Blue Sea” to “take Me.” She

promises to bring him all her feeder brooks in return. A little earlier in F206

“Least Rivers – docile to some sea,” she refers to her lover as “My Caspian.”

In

this poem Dickinson is much more specific. The River becomes but an individual “Drop”

that soon loses her own identity – or at least her “locality.” She no longer

has a place of her own: only that within the vast waters of the ocean. However,

small and insignificant as this drop is, she believes that by merging with the “all”

she will be somehow enlarged herself. Perhaps this idea came to Dickinson via

Transcendentalists such as Emerson or Thoreau who spoke of such notions as losing

particularity within a more cosmic sense of life.

|

| Amphritite is keeping an eye on her husband, Lord Poseiden |

But

then the poem becomes a bit pathetic. Background: Dickinson sent this poem to

Samuel Bowles, a man she certainly had strong feelings for – at the least.

Bowles, however, was married. Poseidon, Greek god who ruled the sea was also

married – to Amphitrite. Dickinson ends the poem by saying, “okay, let’s forget

about the wife for just a moment. Can you somehow still accept me?” The image

of the Ocean smiling at the little drop’s presumption followed by the pleading

of the drop – who knows she is being a bit out of line – makes us feel a little

sorry for the poet.

But

we shall forgive her for she suffered much and wrote much splendid and

hair-raisingly good poetry from that place of pain. This may not be one of the

good ones, but it is interesting in its evocation of Eastern mysticism as well

as in its intimations of the poet’s personal life.

The

poem is composed in three stanzas, each in iambic tetrameter for two of their

three lines and then a third short line. In the first two stanzas it is iambic

dimeter. In the last, Dickinson ends with a spondee: “Pleads – ‘Me’?” The assonance of "Plead" with "Me," along with the rhymes with previous stanza-end rhymes ("Thee" and "be") serve to emphasize the "Me." This emphasizes a hope that while the drop may become submerged in a

greater body of water it still wants its own consciousness – its sense of “me.”

And that is not really so transcendental after all!

03 May 2012

A Mien to move a Queen –

A

Mien to move a Queen –

Half

Child – Half Heroine –

An

Orleans in the Eye

That

puts its manner by

For

humbler Company

When

none are near

Even

a Tear –

Its

frequent Visitor –

A

Bonnet like a Duke –

And

yet a Wren's Peruke

Were

not so shy

Of

Goer by –

And

Hands – so slight,

They

would elate a Sprite

With

merriment –

A

Voice that alters – Low

And

on the Ear can go

Like

Let of Snow –

Or

shift supreme –

As

tone of Realm

On

Subjects Diadem –

Too

small – to fear –

Too

distant – to endear –

And

so Men Compromise –

And

just – revere –

F254

(1861) 283

|

| The proud Duke of Orleans and his "bonnet" |

This

sprightly poem celebrates a woman of many faces and moods. She can adopt an

appearance and manner that would “move a Queen,” behave with the noble pride of

the Duke of Orleans – and with his “Bonnet” or crown as well. On the other hand,

she is “Half Child” and is just as easy among common folk as she is among the

gentry. She can be shyer about her appearance than the wren with it’s humble

peruke, or wig. Her hands are so tiny that a fairy would laugh at them.

We

are also told that this quixotic creature cries when alone – and frequently,

too.

Her

voice is supple: she can be low and musically hushed as a snowfall or else as

bold and strong as a ruler speaking on royal matters to his people. She is “Too

small – to fear” yet too remote, “Too distant – to endear” herself to people.

She is stuck in some odd place: people neither fear her nor have warm affection

for her. Instead she is revered – which is a distant sort of admiring respect.

Who

is this person? Could it be one of Dickinson’s friends? Could it be Dickinson

herself? We know she considered herself humble and small. We also know that she

harbored ideas about her inner royalty and divine gift of poetry.

I

think she is writing a poem about herself, mainly because of the very light

tone. The rhymes border on the humorous: Queen with Heroine; Tear with Visitor;

Duke with Peruke. The images are lightly cast as well: Heroine, Duke, Wren,

Child. It’s a rather charming portrait, no matter who the subject is. I don’t

think the poetry is worth studying except for the potential insight into the

poet’s self image.

I’ve nothing else – to bring, You know –

I’ve

nothing else – to bring, You know –

So

I keep bringing These –

Just

as the Night keeps fetching Stars

To

our familiar eyes –

Maybe,

we shouldn’t mind them –

Unless

they didn’t come –

Then

– maybe, it would puzzle us

To

find our way Home –

F253

(1861) 224

The

poet, like the night, has a gift that has become so familiar that it risks

being taken for granted. After all, although “Night keeps fetching Stars,” how

many of us make a point of paying attention to them? They are just a familiar

backdrop. In Dickinson’s day, of course, the stars would have been much more

visible since they had only a fraction of the light pollution that most of us

have. We only get to see a vivid night sky when the power is out or if we are

far away from city lights.

|

| Celestial Navigation has brought many a sailor home. |

Dickinson

confesses she has only one thing to bring, and unless she is talking about

flowers she is talking about her poetry. Poems to Dickinson are like stars to

the night sky. In the last stanza she notes that even we might not think we

would miss the stars, we could actually become lost without them. Polaris, the

North Star, is an important directional landmark throughout the Northern

hemisphere. We can also navigate by the constellation’s rotation throughout the

night: they seem to move from east to west, about five degrees per hour (if I

recollect correctly).

The

implication follows that without poems we would also become puzzled about the

way home. That’s a bold and really lovely claim for poetry. Textbooks,

histories, and novels all have their place in teaching us about the world, but

Dickinson implies here that if we want to find our way home – find our way to

the place we truly belong, to a place of truth and solidity – we rely on

poetry. “Tell the truth but tell it slant,” she says in a later poem. There is

a deep truth to good poetry that goes beyond what our scientists and social

workers and philosophers might tell us. So if there were no more poems many

more of us would lose our bearings, just as we would without the presence of

the Northern Star.

02 May 2012

I think just how my shape will rise –

I

think just how my shape will rise –

When

I shall be "forgiven" –

Till

Hair – and Eyes – and timid Head –

Are

out of sight

– in Heaven –

I

think just how my lips will weigh –

With

shapeless – quivering – prayer –

That

you – so late – "consider" me –

The

"sparrow" of your Care –

I

mind me that of Anguish – sent –

Some drifts were moved away –

Before

my simple bosom – broke –

And

why not this

– if they?

And

so I con that thing – "forgiven" –

Until

– delirious – borne –

By

my long bright – and longer – trust –

I drop my Heart – unshriven!

F252

(1861) 237

This

poem continues from the previous one where the lover, as bleeding spaniel, is

wanting its beloved master to know it is about to die of grief and wants to be

back in his good graces. She is

still waiting here for forgiveness and in facts anticipates that her “shape”

will be rising up to heaven by the time that happens. We see the shape rising:

first the hair ascends until out of sight, then the eyes, and finally even the

poor “timid Head” disappear above the clouds. As she goes her shapeless lips

will be still be praying – in a “quivering – prayer” the beloved at last, “so

late” might

consider her worthy of his care, just as Jesus once said the God the Father

cares for every little sparrow.

She

remembers the “Anguish” of her tormented love. Some things must have gotten

better, for she says that “Some drifts were moved away”: some portion of her piles of

grief, before her heart broke. Her bosom here is “simple” in accordance with

her head being “timid.” But some large “drift” must still block her beloved’s

forgiveness, for she asks, why could those things be forgiven but not “this”?

And

so she ponders the notion of being “forgiven” until at last she is “borne”

away to Heaven by her brighter and more enduring faith in God. Only at this

point can she “drop” her heart. In a last wave of pathos she adds that her earthly

heart will remain “unshriven!” – meaning still unforgiven by her beloved.

It’s

not a memorable poem, and thankfully Dickinson moves beyond this turmoil in her

life – at least to the degree that her later poetry distills grief into a knife

edge of expression.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)